1

WM Report on Recycling

September 2020

1. Overview

Following an in-depth engagement with As You Sow and Trillium Asset Management, in February 2020, Waste

Management

1

committed to publishing this “Report on Recycling” to help identify gaps in plastic recycling

infrastructure, to provide an assessment of WM’s material recovery facilities (MRFs); and to advance a

discussion of WM’s policy and advocacy positions related to plastic recycling issues.

Summary of Process and Results

Gap Analysis. WM enlisted RRS Consultants to conduct research and to gather data on national and regional

recyclable plastic tonnage generation, as well as end markets. WM performed a detailed review of this

information with our commodities marketing team and then used WM’s 2019 sales information as an overlay for

the Company’s material flow.

Data used included U.S. EPA (EPA) 2017 generation data and the Association of Plastics Recyclers’ markets data.

This information was supplemented by RRS Consultants’ expertise, combined with WM’s actual sales

information. Follow up calls to end markets were used to resolve market discrepancies.

We have a high confidence level in the accuracy of this information, but we note that it is affected by many

forces, most importantly, the fluidity of the markets:

• Polyethylene terephthalate (PET) markets are the most consistent. PET plastic is used in the textiles

industry, as well as the food and beverage industry (e.g. water and soda bottles, as well as clear plastic

thermoform/deli-trays). Buyers of recycled PET (rPET) plastic tend to be larger companies, with more

consistent purchasing habits.

• High density polyethylene (HDPE) recyclers are smaller and flex between virgin and post-consumer resin

use based on pricing. Virgin HDPE resin is often used for milk and juice jugs, as well as beauty care products

such as shampoo, household chemicals, and industrial cleaning products, while recycled HDPE (rHDPE) is

generally used for durable goods. In late 2019, pricing for post-consumer natural colored HDPE increased

due to brand demand. However, when the post-consumer resin pricing got too high, producers moved back

to virgin resin. As demand fell, so did pricing.

• Polypropylene (PP) is often recycled by HDPE recyclers and is dependent on virgin pricing. PP is a versatile

plastic used for food packaging (e.g. yogurt cups), paint “cans”, and in other commercial and industrial

applications. PP resin is growing as a resin used in packaging, and WM saw a 10% increase in PP tons processed

at our MRFs in 2019.

Post-consumer resin competes with virgin resin for use in products and packaging. Pricing sensitivity by brands

prevents packaging manufacturers from charging more for packaging that uses post-consumer content (PCR),

which may limit the use of PCR feedstock when virgin prices are low.

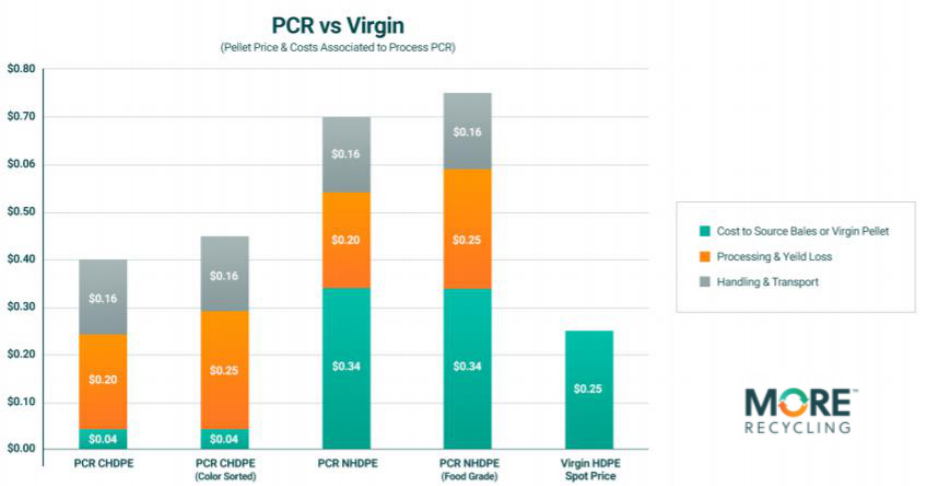

The following chart by More Recycling compares post-consumer polyethylene resin pricing to virgin resin pricing.

It offers a glimpse into the challenge of growing post-consumer plastic recycling, and the particular challenge

associated with using PCR in food-grade packaging, when recycled plastic is more expensive than virgin

plastic/resin.

1

Waste Management, Inc. is a holding company, and all operations are conducted by its subsidiaries. References to

“Waste Management,” “WM,” or “the Company” refer to Waste Management, Inc. and its consolidated subsidiaries, unless context provides otherwise.

2

It is important to note that while this report on recycling provides an up-to-date market assessment for these

plastics in the U.S., it is a snapshot in time and may look very different in a year with new market entries, the

exit of some end markets, and other market shifts.

WM MRF Review. WM categorized its single-stream MRFs into four tiers of facilities based on investment and

processing capabilities, creating a chart of our tiered MRFs. As summarized in this analysis, by 2023, we

anticipate that 91% of WM’s single-stream tons will be processed at MRFs where we have invested in updated

equipment.

Policy and Advocacy Position. Finally, WM compiled its historical and current approach to policies around

recycling. WM is primarily focused on efforts to help ensure a high-quality inbound recycling stream and on

creating end-market demand for recyclables. We describe our efforts to achieve these goals and provide an

update to our plastic exporting policy. WM’s position on Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) has been

described, as well. Both of these policies have been posted on our website.

3

1. Gap Analysis

WM worked with RRS Consultants (RRS) to research and verify flows and markets for plastics generated and

recycled in the U.S. This information was organized by EPA Region.

National overview

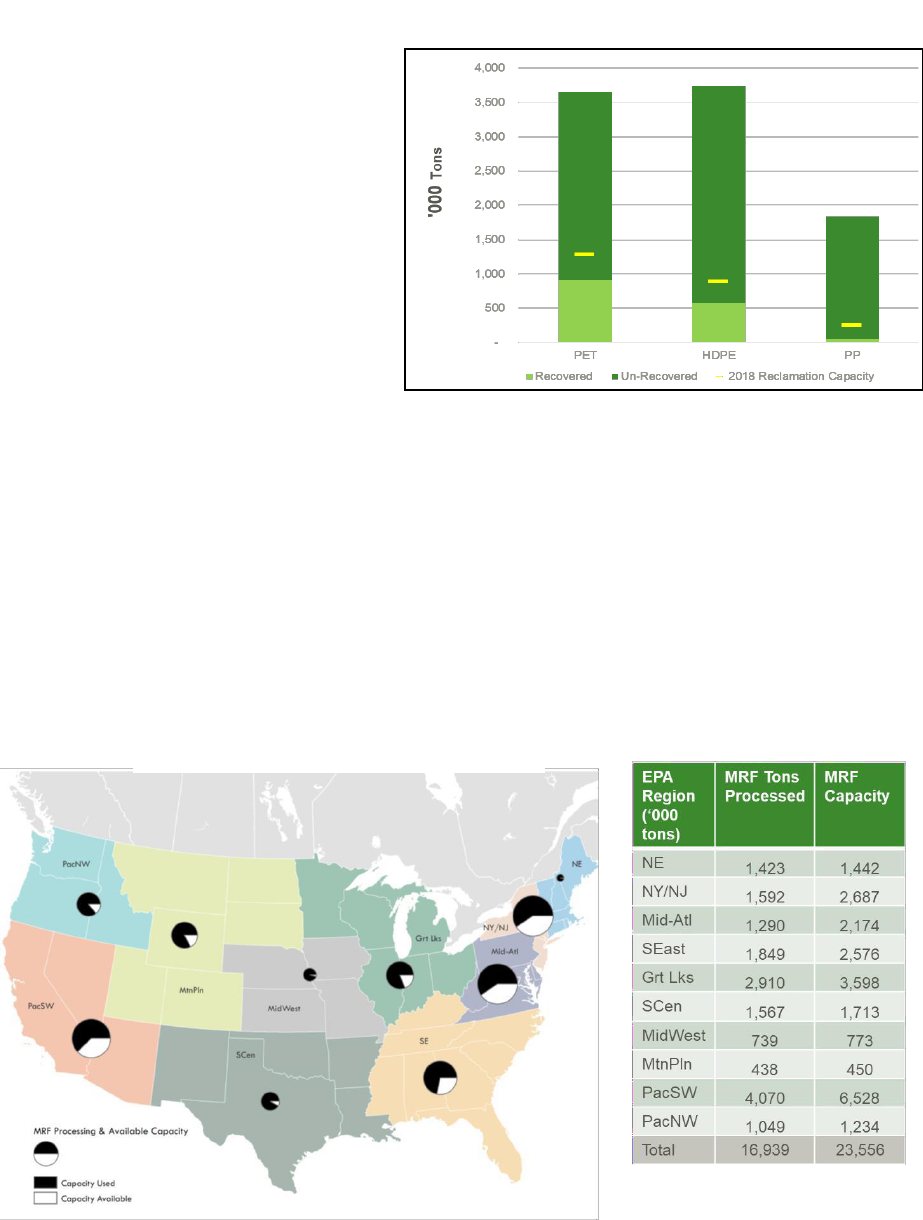

We first analyzed the total amount of PET, HDPE

and PP packaging material in the U.S. Figure 1

describes the material recovered for recycling, the

material that is not recovered, and the total end

market (reclaimer) capacity. This data was compiled

by RRS and includes market information from the

National Association for PET Container Resources

(NAPCOR) and the Association of Plastic Recyclers

(APR). For each of these resin types, there is a

significant gap between total tons generated, tons

recycled, and total reclaimer capacity.

PET reclaimers tend to be well established in the

marketplace. Conversely, there are many more

HDPE reclaimers, and they are more likely to enter and exit the marketplace more frequently, as supply and

demand fluctuates. Further complicating the story is the fact that many HDPE reclaimers also process PP.

Because HDPE and PE have the same density (e.g. the same float/sink systems), plastic reclaimers can use the

same equipment to recycle either resin type, adding a challenge for collecting accurate end-market information.

As PP has grown in use, investments in recycling infrastructure have grown and recycling programs have begun

to grow.

Regional Overview

We next studied total U.S. MRF capacity by EPA Region. Figure 2 describes the recyclables processed through all

MRFs in each EPA region of the U.S., along with the total MRF capacity. This analysis indicates 6.6M tons of

excess MRF capacity in the U.S.

Figure 1: Total Reclaimation – PET, HDPE & PP Gap Analysis

Figure 2: Total U.S. MRF Capacity and Tons

Processed

4

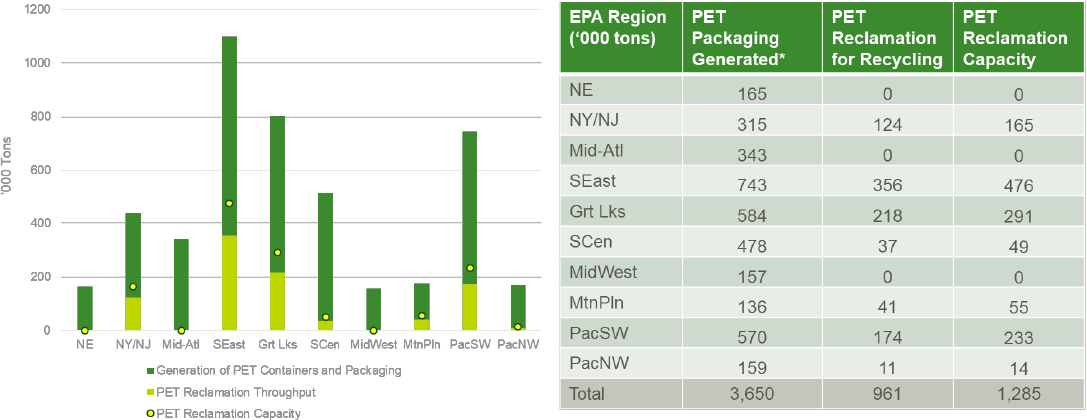

PET Generation, Reclamation and Capacity by Region

A study of PET generation, recovery and total capacity by region highlights the significant differences between

areas of the country where most of the nation’s recyclables are generated compared to the location of end

market processors. Figure 3 highlights PET generation, reclamation and capacity by region.

Figure 3: PET Generation, Reclamation and Capacity by EPA Region

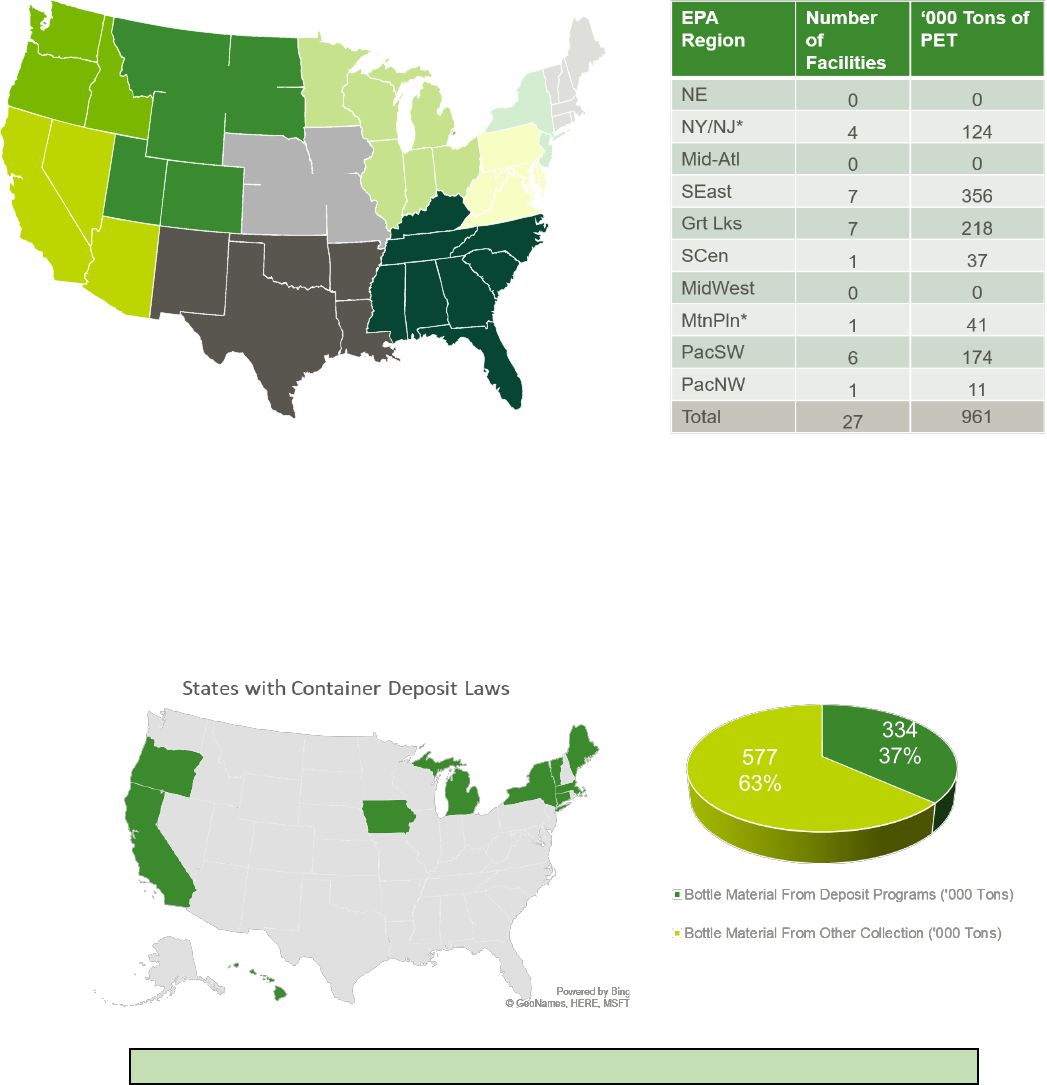

PET markets and capacity vary by region, with most market capacity (by number and by tons recycled) located in

the Pacific Southwest, NY/NJ, the Southeast and the Great Lakes regions (Figure 4). Bottle bills play an important

role in PET recycling in the U.S. Reclamation in the Pacific Southwest is exclusively in California and is focused

primarily on deposit material, with PET collected in curbside programs being shipped to the Southeast for

recycling. About 25% of the capacity in the Great Lakes region and all of the capacity in New York and New

Jersey is deposit material, with processing in their regions.

There is no PET reclamation capacity in EPA’s NE, Mid Atlantic or Midwest Regions. Supply, infrastructure cost,

and demand economics determine the location of PET reclaimers. Since bottles collected for recycling in the

Northeast originate in bottle bill states, they are cleaner and are more likely to be recycled back into bottles.

Bottle-to-bottle recycling requires more extensive processing to meet the FDA requirements for food-grade

resin, resulting in facilities built to accommodate bottle bill-grade material. PET collected in bottle bill programs

in the NE travels to centralized processing facilities in NY/NJ, while curbside PET is sold into the SE.

In California, PET is collected through the state’s container redemption program, as well as the curbside system.

California’s unique redemption system includes varying funding mechanisms for bottles collected through

curbside programs, with funding helping to offset the cost of curbside recycling. And PET collected through

Oregon’s bottle bill program is recycled in Oregon, while Washington’s PET is sold to markets in British Columbia

and the Southeast, depending on pricing. Figure 12 describes PET flows in the U.S.

The historically high value of PET has allowed for shipment of baled product to a wide range of markets (see

figure 12). PET in the Midwest is shipped to centralized reclaimers closer to the largest end markets for

curbside material. As with other recyclables, PET is a commodity, and when the benefits of lower-cost

processing exceed the cost of transportation, it will move to the highest value end market.

* Containers and Packaging

5

As the export markets for this commodity began contracting in 2013, more reclaimers have come online in the

U.S., with locations strategically located according to manufacturing demand. Reclaimers for food-grade PET

tend to be located in proximity to bottle bill states, while reclaimers for most PET collected in curbside programs

are located near markets for textiles and other non-food manufacturing uses.

Recycled PET resin (rPET) is used for a variety of products, ranging from carpeting, clothing, films, strapping and

bottles. Most food grade, bottle-to-bottle rPET is made from PET collected in the ten states in the U.S. with bottle

bills.

Figure 4: PET Markets

Figure 5: PET Recycling – Deposit vs Curbside

Deposit Program Tons (334,000) + Other Collection Tons (577,000) = Total Tons (911,000)

New

England

NY/NJ

Mid-Atlantic

Southeast

Great Lakes

South Central

Midwest

Mountains

and Plains

Pacific

Southwest

Pacific

Northwest

Sources: NAPCOR, RRS End Market Database

*Includes Canadian Facilities that purchase materials from the US

6

While more PET is collected for recycling from non-deposit states, most PET that is recycled into new bottles

comes from those states with bottle bills. Bottle bill material is cleaner and requires less processing. Only 21%

of the PET collected for recycling in the U.S. is made into food grade bottles. The vast majority of PET from

curbside recycling programs is primarily used in non-bottle products, such as carpeting and clothing. The largest

reclaimers are fiber markets in the Southeast who purchase PET from curbside programs.

Figure 6 includes all PET end uses, including products made from PET collected in both container deposit and

curbside programs.

Table 6: PET End Uses

7

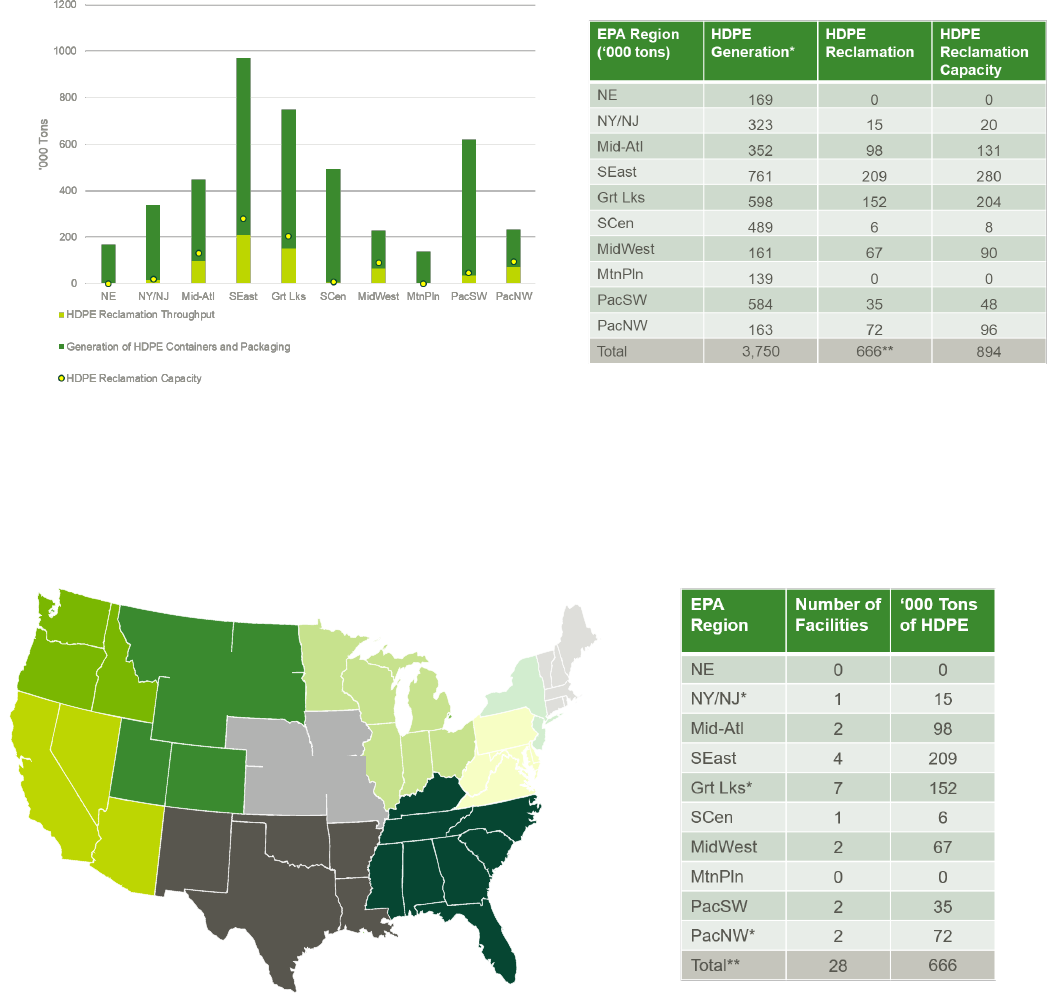

HDPE Generation, Reclamation and Capacity by Region

Similar to PET, the regions of the U.S. generating the greatest volumes of HDPE do not necessarily coincide with

end market locations. Because recyclables are commodities, they are bought and sold based on supply and

demand conditions. Commodity values combined with shipping cost determine the flow of HDPE in the U.S.

Figure 7 highlights HDPE generation, reclamation and capacity by region.

Figure 7: HDPE Generation, Reclamation and Capacity by EPA Region

Sources: EPA, APR, ACC, RRS End Market Database

* Containers and packaging

** Numbers not exact due to small generators/rounding

The largest HDPE volume is generated in the Southeast, Great Lakes, South Central, and Pacific Southwest, while

the greatest market capacity is in the Southeast and Great Lakes regions as shown in Figure 8.

Figure 8: HDPE Markets and Facilities by Region

**12,000 tons from 7 small reclaimers attributed to no

specific region

New

England

NY/NJ

Mid-Atlantic

Southeast

Great Lakes

South Central

Midwest

Mountains

and Plains

Pacific

Southwest

Pacific

Northwest

*Includes Canadian Facilities that purchase materials from the US

8

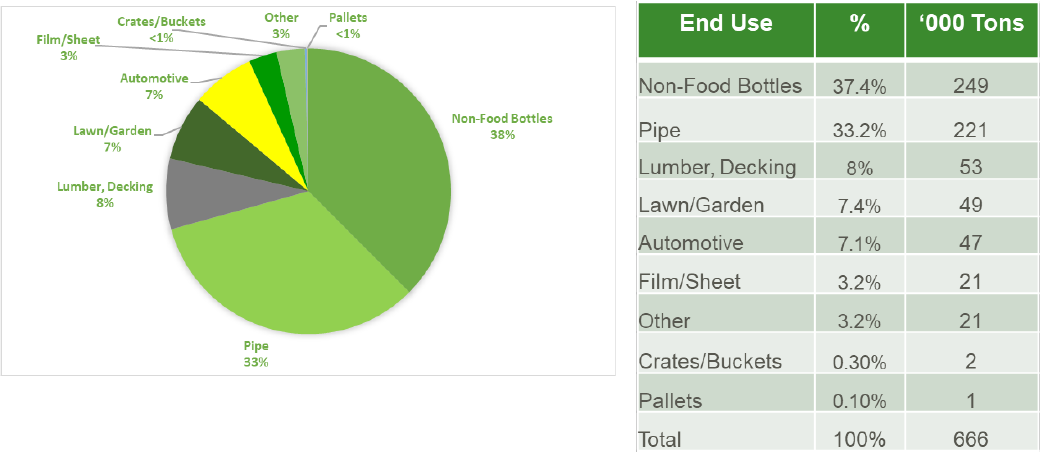

Figure 9 demonstrates that very little HDPE is processed into food grade products, with most being used for

infrastructure projects and durables goods, such as piping, or for lawn, garden or automotive uses. We are

aware of two reclaimers who have been approved by the FDA to manufacture food grade HDPE resin. While

these volumes are negligible today, we expect them to grow over time. One is located in the Southeast, and the

other in the Pacific Southwest.

Figure 9: HDPE End Uses

9

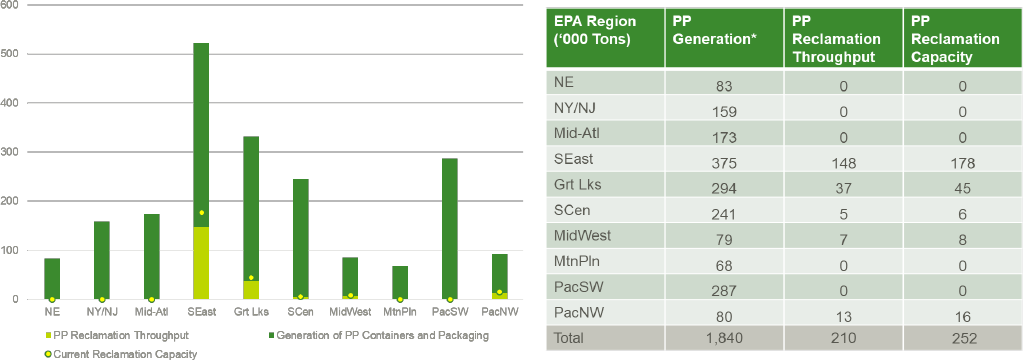

Polypropylene Generation, Reclamation and Capacity by Region

Polypropylene generation has grown in recent years due to the versatility of the resin in packaging. The

commodity value of recycled PP resin has been competitive compared to the price of virgin resin, which has

resulted in a growth of PP recycling over the past several years. More reclaimers are processing PP, and the

commodity value of this resin has made it attractive for MRFs to sort out of their inbound feedstock.

Figure 10 shows that PP generation, reclamation and capacity is strongest in the Southeast region due to the

high concentration of lower-cost manufacturing of end products using PCR. Companies in the Southeast tend to

manufacture products and packaging that can accommodate post-consumer resin. This is an important

reminder that the recycling process is only complete when recyclables are manufactured into new products, and

the environmental benefits are realized by offsetting the use of virgin materials.

The Southeastern U.S. relies heavily on PCR for their manufacturing industry, contributing to their overall

economy. Because of the overlap between HDPE and PP manufacturing (reclaimers are able to process both

HDPE and PP using the same equipment), the same economic principles apply to both resin types.

Figure 10: PP Generation, Reclamation and Capacity by EPA Region

Sources: EPA, APR, ACC, RRS’ End Market Database *Containers and Packaging

Most PP collected in curbside recycling programs consists of tubs, lids and bulky rigid items. PP makes up

approximately 55% of mixed #3-7 plastic bales, so MRFs will often sort PP from mixed plastics. Secondary plastics

recyclers such as Titus (Southern California) also extract PP from their inbound #3-7 plastics.

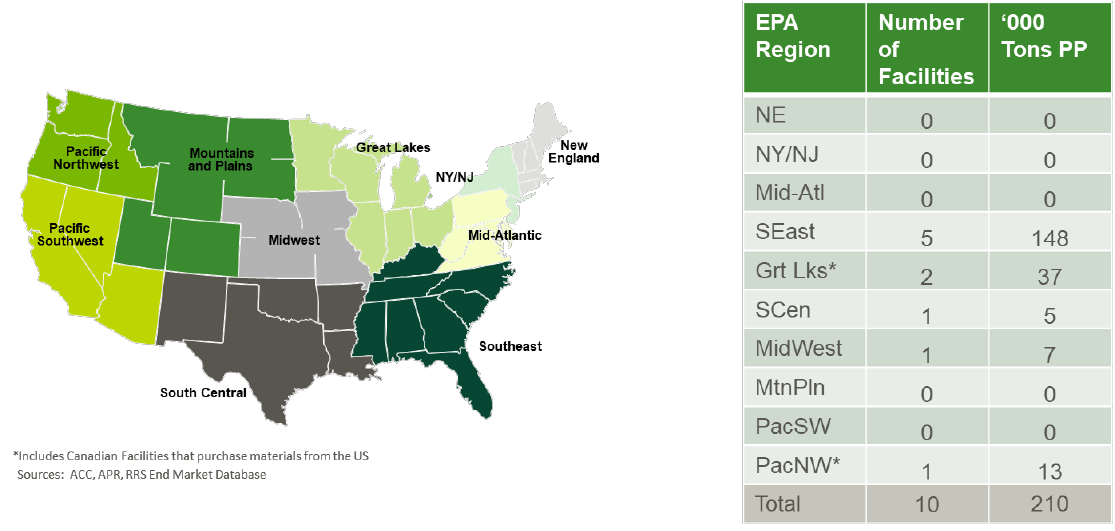

Figure 11 highlights the relatively small number of reclaimers who are responsible for recycling the largest volumes

of PP – as much as 60% of the PP recycled in the U.S.

10

Figure 11: PP Markets

Typical applications for recycled PP include the automotive industry, crates, buckets, piping, lawn and garden

products and other relatively thick-walled injection molded products. Composite products, such as lumber and

rail ties are also manufactured from recycled PP. A negligible amount of the PP is used in packaging due to the

high amount of mixed color in recovered PP. While no recycled PP is currently used in food packaging, the FDA

has allowed at least one reclaimer to use approved PCR PP in cosmetics and deodorant packaging. Emerging

technologies, such as PureCycle, may support a shift in this trend through use of technology that can remove

coloring and other additives to create a virgin-like resin.

11

Waste Management’s Plastic Flows

Waste Management compiled the volume of PET, HDPE, and PP that the Company processed and sold from its

MRFs in 2019. The tons sold from each MRF were categorized separately by resin and by EPA regions. To

understand material flows of WM’s plastic, we also created an inventory of our 2019 end markets sales for each

plastic type by EPA region. This data was used to map the movement of WM tons generated by EPA region.

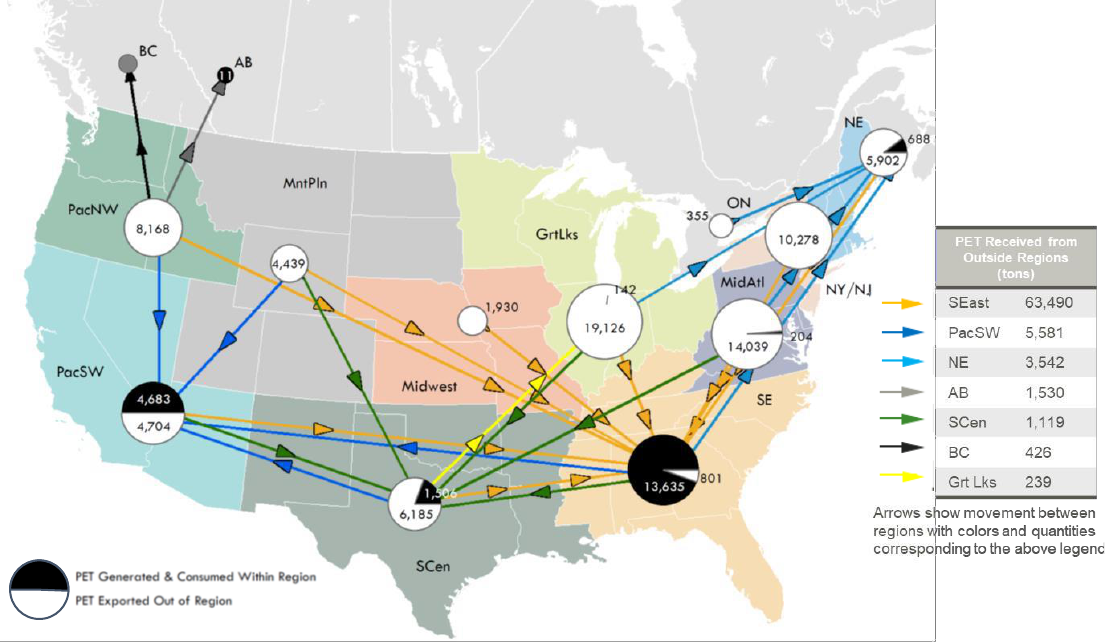

PET. Figure 12 provides the flow of WM’s PET sold in 2019.

• The circles report the number of tons of PET that WM sold from the color-coded EPA Region.

• The white portion of the circle are the tons that moved to other regions for recycling, and the black portion

are those that were processed within the same region.

• The table on the right lists the total amount of PET used within each region.

• Arrows show the movement between regions. The color of the arrow corresponds to the color of the region

PET is sold into.

Figure 12: WM’s PET Flow by EPA Region

The vast majority of PET in the U.S. is processed in the Southeast region of the U.S. There are also several

regions of the country into which WM does not sell any PET. Due to the value of the commodity combined with

shipping costs, eighty percent of all of the PET that WM markets from its MRFs is sold into the Southeast region.

For these same economic reasons, none of the PET marketed from our MRFs is sold to end markets in the Pacific

NW, South Central, Northeast, Mid-Atlantic, Great Lakes, Midwest, or New York/New Jersey regions. Other than

the redemption material that WM receives through its California MRFs, WM does not manage bottle bill PET in

12

any other state. Thus, the map does not reflect the flow of PET that is collected through bottle return programs

and sold directly to processors for recycling without flowing through our MRFs.

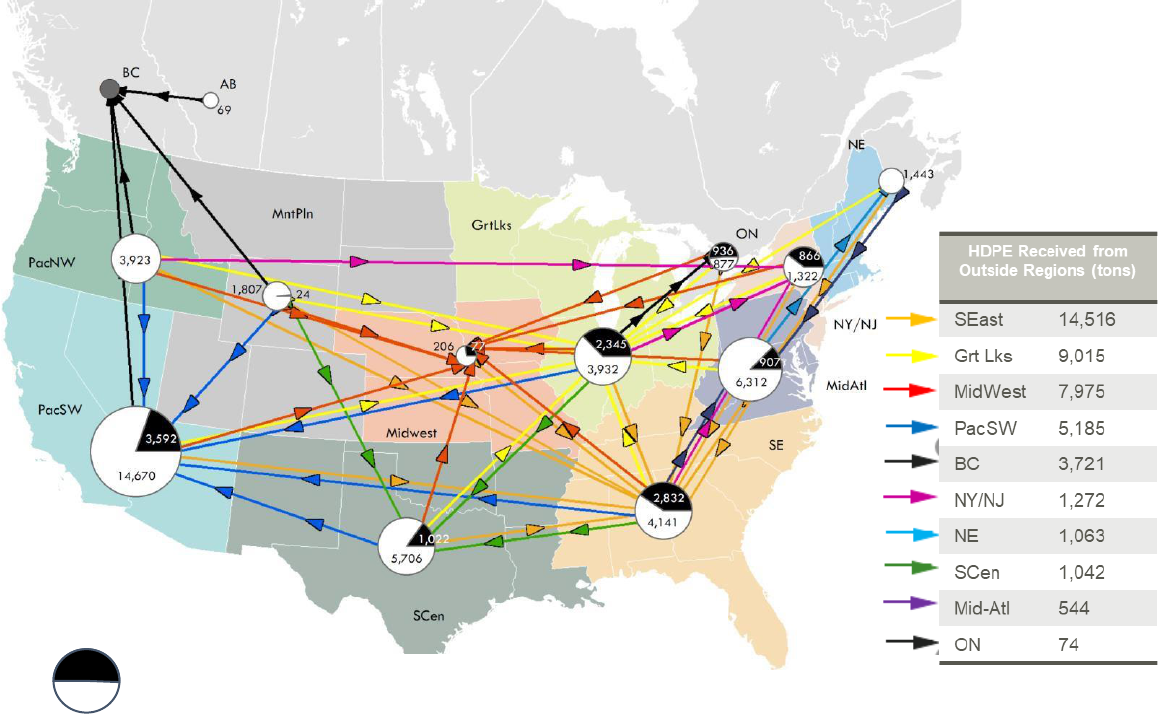

HDPE. The HDPE that WM sells from its MRFs flows to a wide range of end markets across the country. While

WM sells HDPE into several regions of the country, most is sold to markets in the Southeastern U.S., the Pacific

Southwest, the Great Lakes and the Midwest.

Figure 13 describes WM’s HDPE Flow by EPR Region:

• The circles report the number of tons of HDPE that WM sold from the color-coded EPA Region.

• The white portion of the circle are the tons that moved to other regions for recycling, and the black

portion are those that were processed within the same region.

• The table on the right lists the total amount of HDPE used within each region.

• Arrows show the movement of HDPE between regions. The color of the arrow corresponds to the color

of the region HDPE is being sold into.

Figure 13: WM’s HDPE Flow by EPA Region

Arrows show movement between regions with colors and

quantities corresponding to the regional legend

HDPE Generated and Consumed within Region

HDPE Exported Out of Region

13

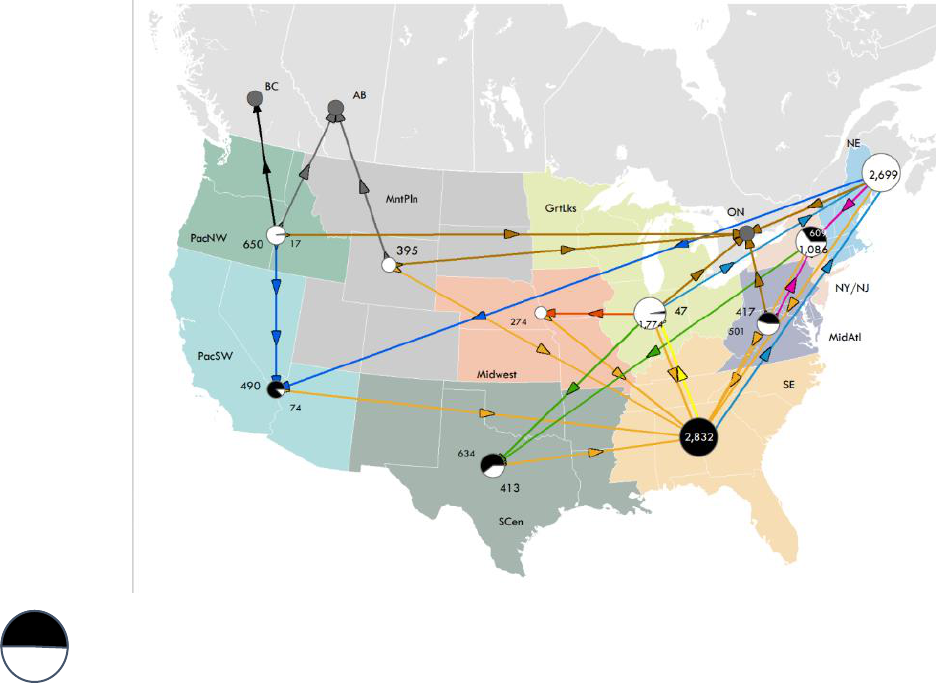

Polypropylene. The amount of PP that WM sold from its MRFs to end markets increased by 10% in 2019,

indicating the growth of PP as a recyclable commodity in curbside programs. HDPE and PP end users are often

one and the same, and their use of post-consumer PP resin is highly dependent on virgin resin pricing. WM sells

most of its PP to markets in the Southeast, the Pacific Northwest, and NY/NJ regions.

Figure 14 describes WM’s PP flow by EPA Region:

• The circles report the number of tons of PP that WM sold from the color-coded EPA Region.

• The white portion of the circle are the tons that moved to other regions for recycling, and the black

portion are those that were processed within the same region. Material flow is a function of supply and

demand pricing combined with the cost of shipping. Because plastic is a commodity, it will move find its

maximum net value market.

• The table on the right lists the total amount of PP used within each region.

• Arrows show the movement of PP between regions. The color of the arrow corresponds to the color of

the region that WM is selling PP into.

Figure 14: WM’s PP Flow by EPA Region

PP Generated and Consumed within Region

PP Exported Out of Region

14

2. WM MRF Overview

MRFs are capital intensive facilities with 20-year depreciation schedules for buildings and 10-year depreciation

schedules for most of the processing equipment, requiring careful planning and long-term strategic investments.

Waste Management maintains a ten-year capital investment schedule used to assess the need for facility

upgrades and/or replacements. Due to land use, permitting, capital cost, and volume requirements, WM

upgrades most MRFs rather than develop new greenfield sites. There are exceptions to this rule and we

continue to make investments in both remodeled and new facilities.

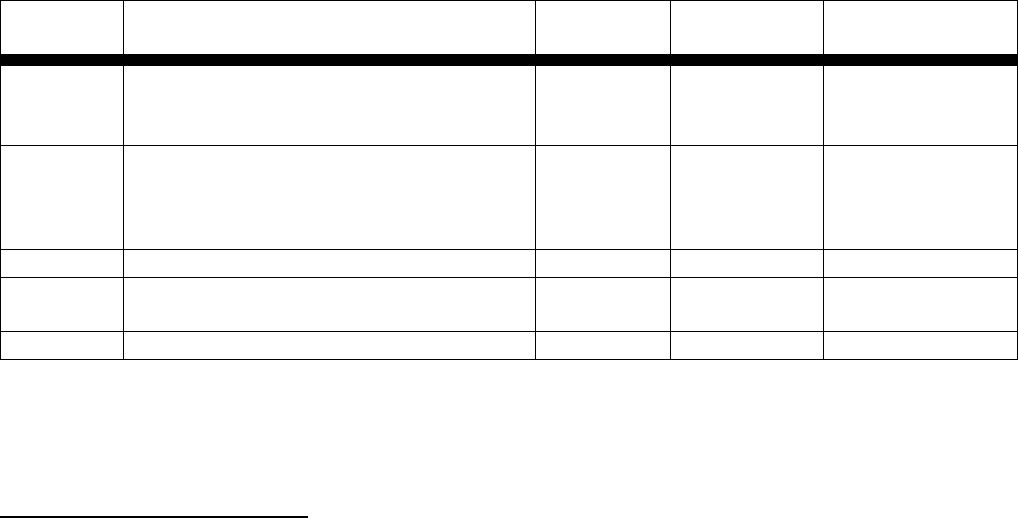

WM has identified and evaluated its single stream MRF inventory, assigning each of its MRFs into one of four

tiers:

Tier 1: WM’s state-of-the-art MRFs starting up and/or being built in 2020

Tier 2: Recently upgraded MRFs with optical sorters, robotics and the newest screen technology

Tier 3: On the list for upgrades within the next 3 years

Tier 4: Not meeting the criteria of Tiers 1-3.

WM continues to invest in equipment to help produce the highest quality outputs and is also investing in work to

clean-up inbound material streams. Our upgrades are designed for efficient production of high-quality outputs for

our end market customers.

Tier

Description

# MRFs

% MRFs

% of MRF tons

1

New facilities opened (or

opening) in 2020

with latest equipment

4

8%

8%

2

Facilities with optical sorter

and/or screen

upgrades within the past 2

years

20

40%

58%

3

Facilities planning investments

12

25%

25%

4

Those facilities have no near-

term plans for upgrades

13

26%

9%

49

100%

100%

Barring any long-term changes in market conditions and recycling volumes, including impacts of COVID-19, WM

anticipates processing 91% of our single stream tons at the 73% of our MRFs where will have improved

processing capabilities as a result of investments in construction and upgrades by 2023.

Implications of these investments

There are many variables that influence the impact of the investments that we make at each of our MRFs, with a

unique analysis completed for each one. For greater context on some of the investments that WM has made

recently at different facilities, we note the following details around recent upgrades.

Examples of MRF upgrades:

• Extensive facility upgrade ($6.5M). In 2019, at one of our larger facilities, we installed non-wrapping

screens, the latest optical sorting and robotics technology, and new conveyors to increase recovery of the

non-fiber components of the stream, including various plastic resins. Additionally, the investment was

15

designed to increase throughput, reduce our operating costs, and provide higher quality fiber commodities

to help ensure long-term marketability. The new equipment is also designed to better separate non-fiber

material and brown fiber such as cardboard from mixed paper.

The resulting benefits from this $6.5M investment included improving the outbound paper quality. We were

able to reduce brown fiber in the mixed paper from 25% brown to less than 3% allowing us to improve end

market options and the value of our paper being sold to market. Our aluminum and PET quality also

improved quite dramatically with the addition of the new equipment, generating a corresponding increase

in value.

A great way to summarize the benefits of this investment and improvements in throughput, recovery, and

quality is that using current commodity prices, our blended value per ton increased by approximately

$11.00, which benefit our inbound customers either through revenue pass-back programs, or reduced

processing fees, the environment through increased capture rates, and our shareholders with better

performance.

• Small to mid-size project ($1M-$3M): In many instances, relatively small projects can have an impact on the

volume and quality of material recovered. In this example, WM upgraded its optical sorting system at one of

our older facilities. Before the upgrade, the facility had a PET plastic capture rate of 94%. After the upgrade,

with a capture rate of 98%, sorters on the container line have reported that they no longer see any PET on

their sorting station, which allows them to focus on HDPE capture. This has allowed us to extract more

valuable colored and natural HDPE from the container line while the new optical sorter is capturing most of

the PET.

Other effects of MRF investments

• Reduction of contamination rate at facilities. In the first example above, the site upgrade provided for a

better separation of fiber from non-fiber primarily due to the non-wrapping screen (plastics and other

materials don’t wrap around the screens so the containers fall through the openings to the correct location).

At this facility, contamination contained in materials shipped is now 6.3% after the upgrade, compared to

9.3% in the first nine months of 2019.

• Increase in volume processed. Facility upgrades generally increase throughput, allowing the recycling plant

to process more tons across the same time period. As such, there are complementary ways that facility

upgrades can help achieve a goal of increasing overall volumes:

o Building additional capacity to process single stream material in regions with underperforming recycling

programs can help lay a critical infrastructure foundation for successful recycling programs. The caveat is

that collection investments must match facility investment. We see new tons collected where there is a

match between single stream carts, collection vehicles, processing infrastructure, and high-quality

education and outreach efforts.

o Education and technology to reduce inbound contamination plays an important role in freeing up space

to process more recyclables as well as increasing the value of the materials.

o Upgrading bins to carts makes recycling more convenient, increasing both participation and the volume

collected. Studies consistently show a 40% increase in recycling with a transition to cart- based single

stream recycling.

16

o Creating demand for materials plays a fundamental role in growing recycling tons. Polypropylene

demand is a great example of new tons being profitably recycled due to growing end market demand.

Glass offers another example. As demand for glass has constricted, this material has been dropped from

curbside collection programs, reducing the overall tons collected. New end market demand for glass

could help glass return to recycling programs, increasing overall tons recycled.

Importantly, adding supply without addressing demand is a recipe for failure because recycling systems are

inelastic. Once a material is added to a curbside program, if there is no relationship between the collection and

the end markets, recyclability is stymied. This is evidenced by the current mixed paper and glass markets where

the supply far outstrips the demand, reducing the economic viability of the process. Market demand

development for products with post-consumer content is critical to ensure that material will be manufactured

into new products.

Investments to increase the types of materials processed at MRFs

It is important to point out that it only makes sense for MRFs to invest in infrastructure to recycle those

materials with enough volume to create full loads on a regular basis and with viable end markets. Materials that

fit that description in the U.S. include cardboard, aluminum and tin/steel cans, PET, HDPE and PP bottles, and

glass (where end markets exist). Mixed paper is an anomaly - the volume exists, but there is not sufficient

domestic market demand to handle our current supply. We are looking for domestic demand to adjust in the

next few years to compensate for the global market redistribution.

PP is a new addition to this list. In the past, either PP was not an acceptable material, or was part of the mix of

plastics #3-7. While today there is minimal (or no) domestic demand for plastics #3-7, demand is growing for PP.

WM has added optical sorters at many of our single stream MRFs to capture PP, and we also are capturing this

material at several commercial MRFs, increasing the recyclability of this material. In 2019, WM sold approximately

6,000 tons of PP, which is a 10% increase over our 2018 tons sold separately.

17

3. Policy Overview

Waste Management has played an active role in the public policy dialogue around recycling. Over the past

several years we have worked with stakeholders along the supply chain to learn about the various challenges

and opportunities for improved recycling. As a result of this engagement, as well as extensive research, we have

developed a consistent and transparent approach to recycling policy.

Our role in the supply chain is to manage material responsibly at end-of-life, and to help our customers know

how they can support sustainable recycling programs. Our efforts have been focused around achieving these

goals.

Quality of Recyclables

Perhaps no company has done more to improve the quality of the material collected at the curb for recycling

than WM. Our Recycle Right program (https://www.wm.com/us/en/inside-wm/recycle-right) has become a

valuable resource for our customers, complete with widgets and immediate customer feedback.

Providing education to customers about contamination of recyclables at the curb has resulted in a 30%

reduction of inbound contamination at our recycling facilities – from almost 25% to just over 17%. WM recently

adopted a new 2025 goal of further reducing inbound contamination to no more than 10% by 2025. Our

education programs are key to reaching this goal.

Demand for Recyclables

For over a decade, Waste Management has worked with packaging designers and product manufacturers to

support the concepts associated with designing for recyclability. We are actively engaged in national policy

discussions to encourage recycling and end-market development for recycled products.

In 2019, WM took several actions to support demand by increasing end markets for materials made with post-

consumer content.

• Cart Purchasing Program. In early 2019 Waste Management’s purchasing department began working with

its primary cart supplier to use post-consumer plastic from curbside recycling programs in plastic curbside

carts. The testing was completed in 2019, and WM began to purchase curbside carts made with 10% post-

consumer content in early 2020.

• Demand Champions Program. WM signed on to the Association of Plastic Recyclers’ Demand Champions

program. The Demand Champions program requires that we increase our purchasing of products with post-

consumer content to increase the amount of plastic that is recycled, driving demand for post-consumer

resin.

• EPA’s America Recycles Day. Waste Management has been actively engaged in EPA’s multi-year Recycling

Framework process that started on America Recycles Day in 2018. WM has been the only waste/recycling

company to actively engage in these efforts. We participated on the End-Markets Working Group Steering,

helping to develop a national framework proposal to support the development of end markets as part of

EPA’s effort to advance the recycling system in the U.S. WM has continued to play an active role in

supporting EPA’s framework at it has evolved, and we promoted the need to increase market demand for

post-consumer content at 2019 America Recycles Day events.

We continue to take a leadership role in America Recycles Day efforts, focusing on government procurement

efforts and other demand side opportunities that EPA can support.

18

Increasing Domestic Plastic Recycling

• Design for recycling. WM has worked with organizations such as the Association of Plastic Recyclers and the

Sustainable Packaging Coalition to help educate producers on packaging recyclability. We work directly with

brands/producers/packaging designers to provide input on recyclability. We provide tours of our recycling

facilities and encourage brand/producers/packaging designers to send samples for testing.

• Partnerships. WM works with multiple stakeholders, including governmental agencies and nonprofits, to

increase access to recycling, and to move material to domestic markets. We participate in state stakeholder

processes to strengthen demand for recyclables (Oregon and Washington), and are members of multiple

organizations focused on supply and demand dynamics. Examples include ReMade, the Association of Plastic

Recyclers, Southeast Recycling Development Organization and Northeast Recycling Coalition.

Waste Management’s Plastic Export Policy

Since 2013, Waste Management has been shifting its recyclable plastic sales efforts to domestic markets. By the

end of 2018 we were no longer exporting residential plastics processed through our MRFs to markets outside of

North America, and in the fall of 2019, we formalized our policy of selling residential plastic processed through

our MRFs only to North American markets. The only plastic that WM exports is high-grade, source-separated

commercial film to reputable high-quality end markets. We have recently updated our plastic export policy to

reflect our commitment to moving commercial plastic in accordance with Basel Convention requirements. This

updated policy is posted on our wm.com website (https://www.wm.com/us/en/recycle-right/plastic-exports).

Investments in Recycling

Waste Management invested over $200 million in recycling infrastructure in 2018 and 2019. These investments

include:

• Four new/upgraded single stream recycling facilities, including our MRF of the Future which is designed to

evolve with changes in the waste stream;

• Placement of over 500,000 recycling carts in communities across the U.S., resulting in over 100,000 tons per

year of increased tonnage from residential programs; and

• Over 100 equipment upgrades in our single stream MRFs.

These investments provide additional access to recycling, more efficient processing systems to help reduce the

cost of recycling for our customers and increase the value to our shareholders, and investments in technologies

to process the changing waste stream of the future.

Increasing Effective Recycling

WM enlisted Skumatz Economic Research Associates to review programs to determine the most effective

policies for improving recycling. This report analyzed several hundred municipal programs, resulting in data that

WM has used to support growing recycling programs in the U.S.

Using the research from this study, policies that WM supports include:

• Universal cart delivery – carts are automatically delivered to all households;

• Pay-As-You-Throw trash – variable rates for trash to provide economic incentives to recycle (with quality

control enforcement); and

• Recycling mandates – where enforcement and demand exist.

19

Other policies that WM publicly supports include:

• Recycled content legislation – WM supported minimum content legislation in 2020 including HB 2722 in

Washington (passed by the legislature and vetoed by Governor Inslee on 4.5.2020 due to Covid-19), and SB

2515 in New Jersey (currently being discussed) requiring the use of post-consumer content in products and

goods; and

• Advanced Disposal Fees – A fee on packaging that sends signals to consumers to reduce packaging while

raising funds for recycling education.

Based on data from successful programs in the U.S., with these policy drivers in place, we know how to create

effective recycling programs. Effective recycling requires social, behavioral and economic drivers – and those

communities with effective programs have implemented all of these policy levers.

Lifecycle Thinking

Waste Management spent more than three years reviewing the environmental benefits and the cost associated

with the materials that we manage. The result of this third-party reviewed effort has been a clear understanding

of the opportunity for the best “bang for the buck” associated with recycling the right things correctly.

Moreover, our analysis was a reminder of the need to focus on the waste hierarchy and the benefits of waste

prevention and reduction. WM has communicated these findings in public speaking engagements, in our

Sustainability Report, and at our annual Sustainability Forum.

Legislation

WM advocates for legislation that will support the use of post-consumer content in products and packaging, as

well as funding for more recycling education.

WM has also weighed in on a variety of legislative issues around recycling over the years:

• Material bans and mandates. Waste Management has historically declined to engage in policy debates over

the sale and use of products and packaging. Our role is to manage material safely at end-of-life on behalf of

our customers, not to weigh in on product sale or use.

• Support for public education. Waste Management has been a strong voice of support for federal and state

bills focused on funding and programs to improve the quality of recyclables collected at the curb.

• Support for procurement policies. WM supports bills that would require governmental bodies to purchase

products made with post-consumer content. We also have supported bills that require the use of post-

consumer content in the manufacture of products and packaging in order to help support the development

of end market demand.

• Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR). Well over a decade ago, WM played an instrumental role in the

development of EPR legislation for electronic waste in Washington State and in California. This effort shaped

our current internal policy supporting well-written bills for EPR for Hard-to-Handle (HtH) materials such as

electronics, batteries, CFL lighting, paint, and other items in the waste stream for which there are no funding

or handling systems readily available to consumers. Interestingly, with twenty-five EPR programs on the

books in the U.S., the recycling rate for electronic waste roughly mirrors the national recycling rate at 35.9%

(EPA 2017 Facts and Figures).

20

Research supports our premise that EPR is primarily a funding mechanism used to support programs where

systems are not already in place. The European Union used EPR funding to implement their recycling

programs in the 1990s. Conversely, the U.S. has systems and infrastructure in place in 2020 to handle

traditional recyclables, and EPR has been used as a funding mechanism for HtH materials.

Failure of EPR to create demand. Research into current EPR programs verifies that EPR has not proven effective

in solving for market demand challenges or reducing the use of plastic in the waste stream (Review of Recycle BC

Program Performance, Dr Calvin Lakham, York University, 2020). EPR is a scheme to pay for recycling collection

and processing; there is no mechanism in the design to drive market demand.

Examples include:

o Europe. In the EU, where EPR has been in place for well over a decade, prior to 2017 a large portion of their

recyclable plastic was exported to Asia for recycling. As markets in Asia closed, waste-to- energy has grown

as the solution for managing plastic in Europe.

o British Columbia, Canada. British Columbia’s Producer Responsibility Organization (PRO), Recycle BC,

recently announced that they would change their recycling processor/marketing vendor to try to move their

recyclables to domestic markets. Their producer-funded program has not been able to manage the sale of

recyclables to market.

EPR helps to solve for funding to collect and process material; however, it has proven ineffective in changing

packaging design or creating end market demand. EPR has failed to achieve its primary goal of influencing

packaging design for recyclability. In fact, with fees generally based on weight, lightweight, nonrecyclable

flexible packaging use has grown much faster in the EU than in the U.S.

In 2020, WM developed a position paper on EPR. This position is generally supportive of EPR for hard-to-handle

materials (e-waste, batteries, paint), and supports fees on packaging. WM supports management of recycling

programs at the local level; as such, we may support EPR schemes when the funding is distributed to local

governments. Our full position is posted on our policy website (sustainability.wm.com).